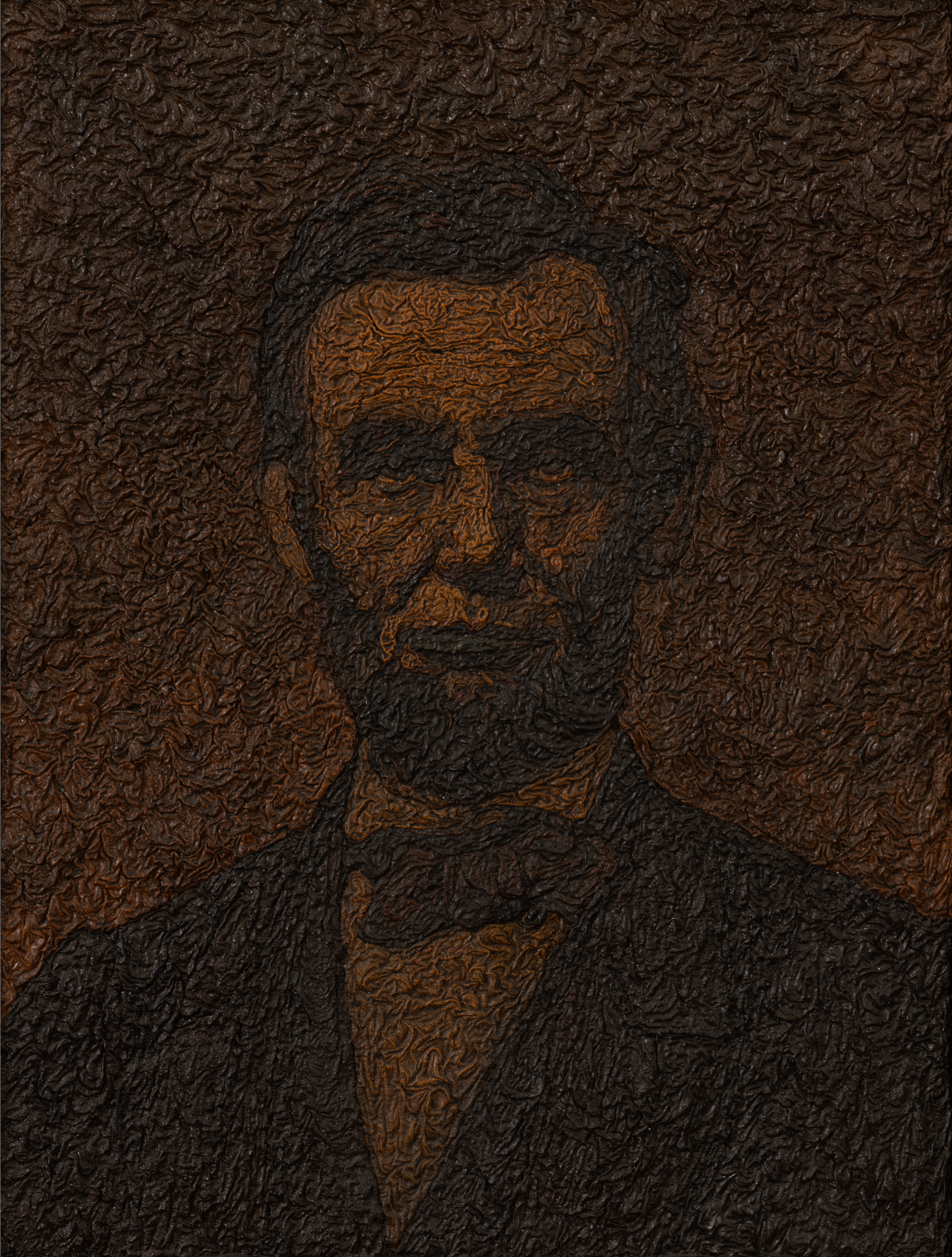

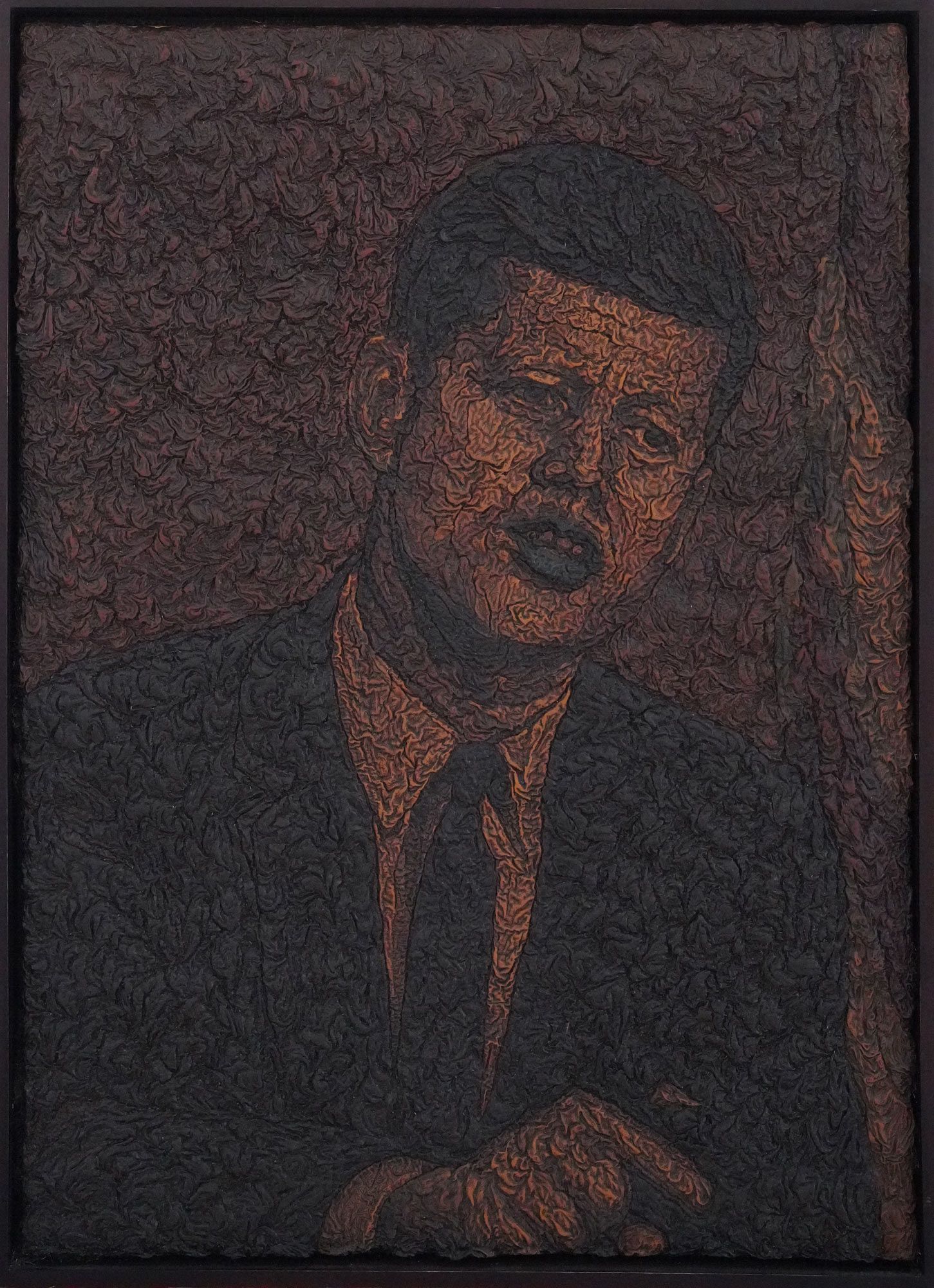

Figures emerge from darkness, not lit but uncovered. American Bog turns to American iconography - presidents, pioneers, flags, and cartoon myths - not to celebrate or condemn, but to see what remains when history begins to decompose.

The subjects are instantly recognisable: Lincoln, JFK, Mickey Mouse, the Frekes. But recognition is not the point. These are not portraits. They are preservations. Wrinkled in thick oil, heavy with time, the paintings behave like the bogs that inspired them - holding the surface while everything beneath begins to collapse.

Like the ancient figure of the Tollund Man - lifted from the peat bog with skin intact but bones dissolved - these works exist in a state of suspended decay. They are intact yet emptied, their stillness more forensic than heroic. The flesh remains. The form lingers. But something vital has already slipped away.

There’s a quiet echo of The Picture of Dorian Gray: surfaces that endure, composed and iconic, while the medium itself records the slow damage of time. Paint wrinkles. Colour sinks. What appears fixed is, in fact, already giving way.

This is not satire, nor protest. There’s no scorn, only sediment. A nation not painted in triumph, but in aftermath. The process becomes part of the message: slow drying, shifting oils, a kind of organic erosion that mirrors the fading certainty of the ideals depicted.

American Bog asks a question without insisting on the answer: what happens to a civilisation when its symbols outlast their meaning? The paintings don’t judge. They preserve. And in doing so, they remind us how thin the distance can be between honour and burial, myth and residue, surface and skin.

Exhibited:

Gallery Broadway 1602, New York 2013.

Further Reading:

American Bog: Erosion, Identity, and the Fragile Image