Installation view – Mark Alexander, Courtesy SAUVAGE & the artist

A Renaissance Person is Something to Be

Any keen student of the biographies of the famous (and that includes photographs of their childhood and other contemporary images) will have noticed their intriguing aura. The more turbulent and problematic the lives, the more attractive they become for literary and visual exploitation. The best and earliest example of this is Giorgio Vasari’s multi-volume Vite [Lives of the Moste Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects] in which the architect and court artist recorded the lives of the Italian High and Late Gothic, Renaissance and Mannerist masters.

Vasari’s account of Benvenuto Cellini’s turbulent life1, for instance, offers a template for today’s ever-increasingly popular artistical bio-pics, such as Florian Henkels von Donnersmark’s full-length Werk ohne Autor (recently filmed in Dusseldorf), depicting the fateful early years of Gerhardt Richer, which were marked by the rise of Nazism and his flight from Germany – repackaged in a blockbuster plot enriched by common clichés about artists’ wild lives. Meanwhile we, the heirs of a past-war era that was still shaken by the rough winds of history, are bidding a nostalgic farewell to its initiation into a ‘smoother’ period of apparent material stabilisation. Byung Cul Han, the South-Korean, Swiss-German philosopher and cultural theorist, holds that this smooth surface reflects a syndrome that goes beyond the socially imperative veneer of iPhone surfaces and Jeff Koons sculptures, and that the modern version of the artistic vagabond-type disdains mere irregularities in his or her c.v. They are passé, démodé, even in the art world. Ultimately this leads to the irony that, even as art is untrammelled, and freed from restriction, the personal freedom of its artists tends to decrease. Benvenuto Cellini2, for instance, would hardly have allowed himself to be constrained to serving the art market in order to achieve an international career. His actual output served him quite well enough.

Installation View: Mark Alexander, Gemäldegalerie, 2016, Courtesy of the artist

The crucial debate between personal creative integrity versus economic profitability, or even the mere actuality of embracing extraordinary difficulties in pursuit of one’s own ideas, also preoccupied the British painter, Mark Alexander, in his final graduation year at the Ruskin School of Art3. In a later conversation recorded by the BBC between Alexander and his then teacher, the Academician Humphrey Ocean, RA, both remember Alexander setting himself the unusually unorthodox task of making ‘the greatest picture in the world’. After extensive preliminary studies, he completed the tondo entitled Golden Wonder. Its wide range of yellow tones are subtly differentiated to create the irresistible impression that this is a bas-relief of hammered gold, at whose centre the head of a chubby, baffled childlooks out at us.

For the artist, this was the closure of another circle. The little boy was Alexander himelf, presented, with typical dry English humour, as the Sun King – only this sun king was born in 1966, in the small southern English village of Horsham, and then raised in the provincial town of Cirencester, where he attended a boarding school catering for children with special needs. Thereafter he started out by working with a silversmith, progressing to an Odyssey that led him from skilled employment in aerospace technology, to a detour teaching Milanese policemen English, and (via a series of coincidences) to a period in the Argentinian gaucho community.

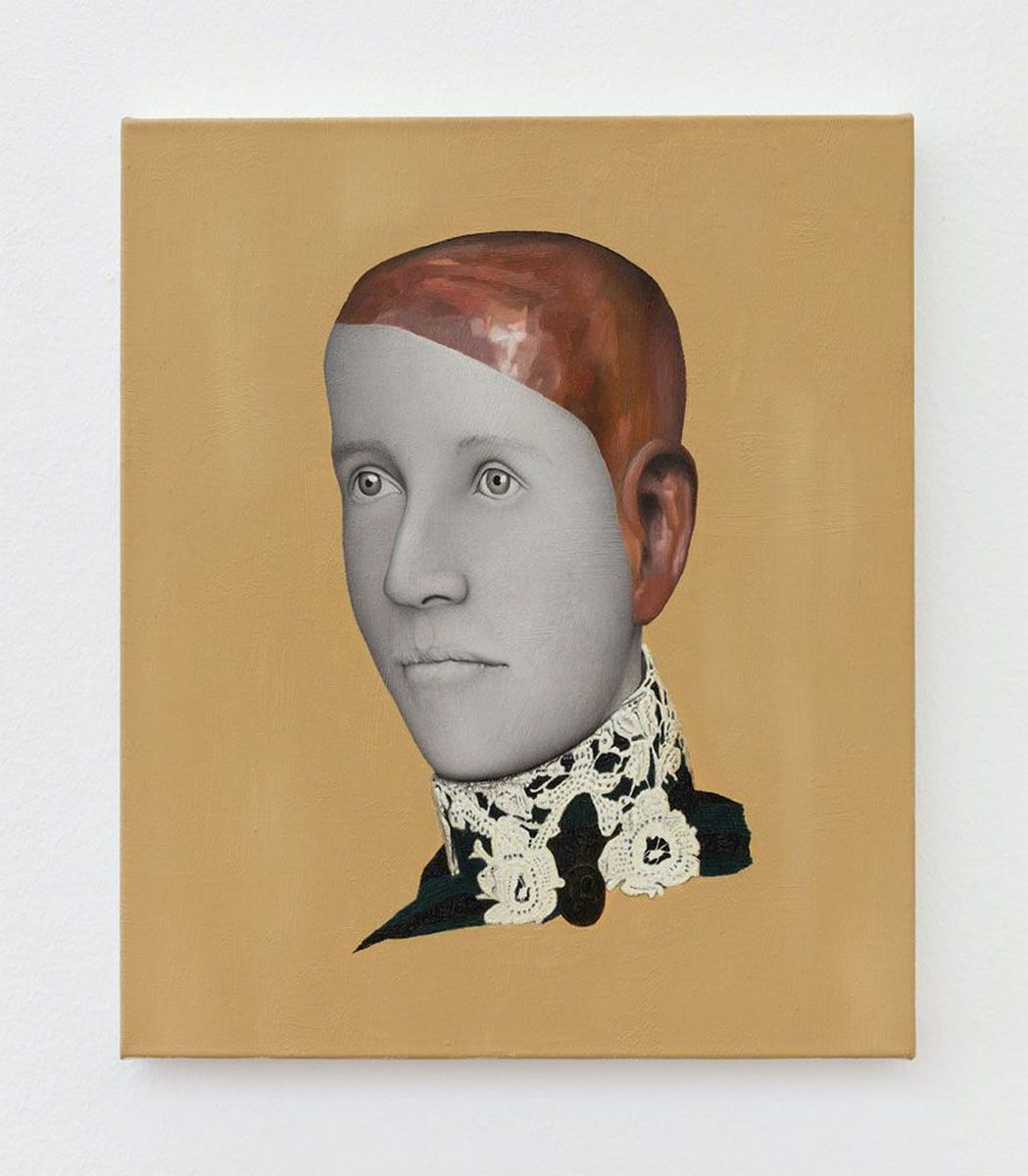

Pioneer, Oil on Canvas, 42 x 35 cm Foto: Johannes Bendzulla

When asked what this initiation period was all about, Alexander’s reply was that he didn’t necessarily want to be a renaissance artist, but a Renaissance Man. Today, his works are in international museum collections like the Pompidou Centre in Paris (which has nine of his paintings). In Germany4 also, after moving to Berlin to take part in various projects, he met Dr Henning Boecker, the scientist, art collector, and founder of Espace Sauvage, which has now included Alexander in the Sauvage exhibition programmes.

At first sight, the paintings that are on view give the impression of a series of large-format photographic collages. In contrast to works by the proponents of classical photorealism, the remarkable degree of naturalistic rendition is not the decisive issue here. The pictures’ underlying premises do not seem to engage with the common dogmas of art schemata. Their slow gestation (often over many months) mirrors an equivalent cultural-historical sustainability that goes beyond mere play with iconographic set pieces or a seamless extension of familiar traditions. For instance, in one picture a female mannequin juxtaposed with a white bird and the evanescent suggestion of a wisp of angelic form engages with the biblical trope of the Annunciation. The picture has undergone an extensive series of far-reaching changes, which mirror the laws of human development by traversing a recognisable course from primitive, childlike draughtsmanship to the highest levels of graphic art.

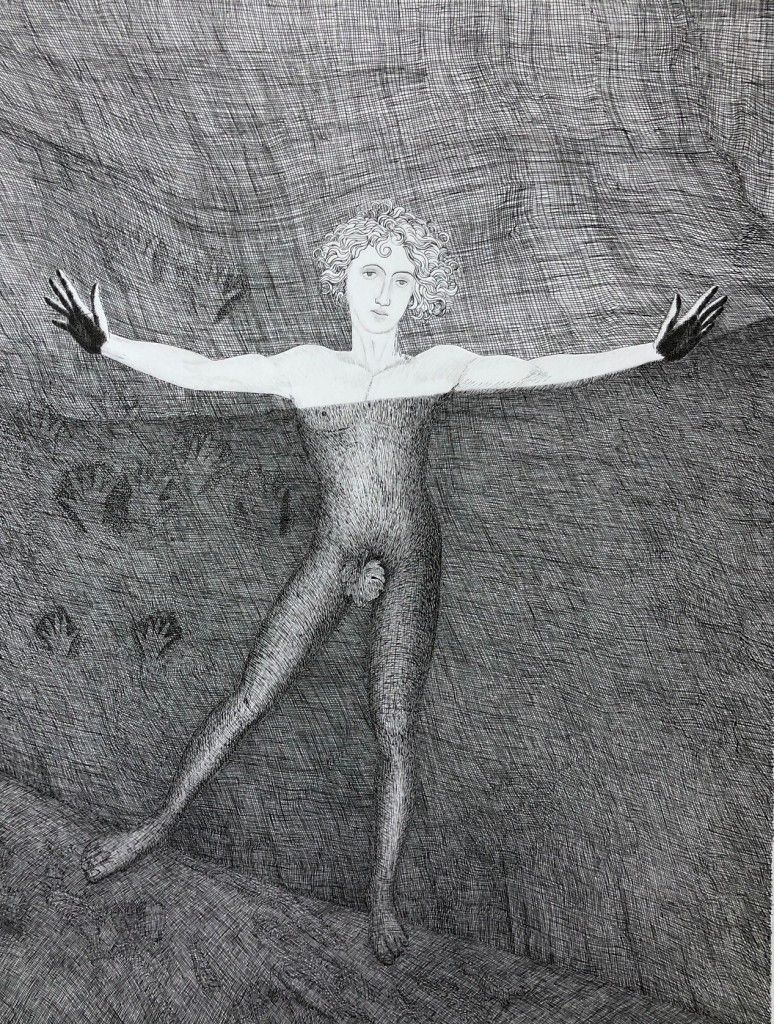

Juxtaposed with these canvases is a single image that comes from a completed series that evokes an even broader time frame. It is reminiscent of the prehistoric cave-paintings which are the earliest artefacts known to man. A youth out of Botticelli appears here, leaving imprints in a cave with soot-blackened palms. The English visionary poet and artist, William Blake, is quoted in the text accompanying the exhibition: ‘Eternity is in love with the productionsof time.’ These works play, profoundly, with the cycles of birth and death, gestation and decay, the growth and collapse of civilisations.

Thus the achievements of Alexander’s work are both technical, aesthetical, and conceptual. Just as the meaning of a historical artefact can outlive the mindset that created it, so the artist himself can create images that reverberate beyond the preoccupations of his time. Alexander’s oeuvre can maintain its place within a eternally rotating cultural-historical continuum: it evokes ideas of cultural glaze and cultural decay, while enacting them on its own account.

Mark Alexander, The Charcoal Dreamers I, 2020, Ink on Paper, 70 x 50 cm, Courtesy SAUVAGE & the Artist

Mark Alexander: Love Between The Atoms

23. April – 12 Juni 2021

SAUVAGE Bastionstraße 5 40213 Düsseldorf

More Articles about Mark Alexander

Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, in: Areté. The Arts Tri-Quarterly. Fiction Poetry Reportage Reviews. Issue Seventeen, Spring – Summer 2005, p. 74-104

Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, ibid., p. 97-98

Ethan Wagner, an introduction to mark alexander, the painter, in: Mark Alexander: The Bigger Victory, Exhibition Catalogue, Haunch of Venison, London, 2005, p. 1

Kelly Grovier, Mark Alexander, Essay, 2009, p.1-2 5 Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, ibid., p. 80