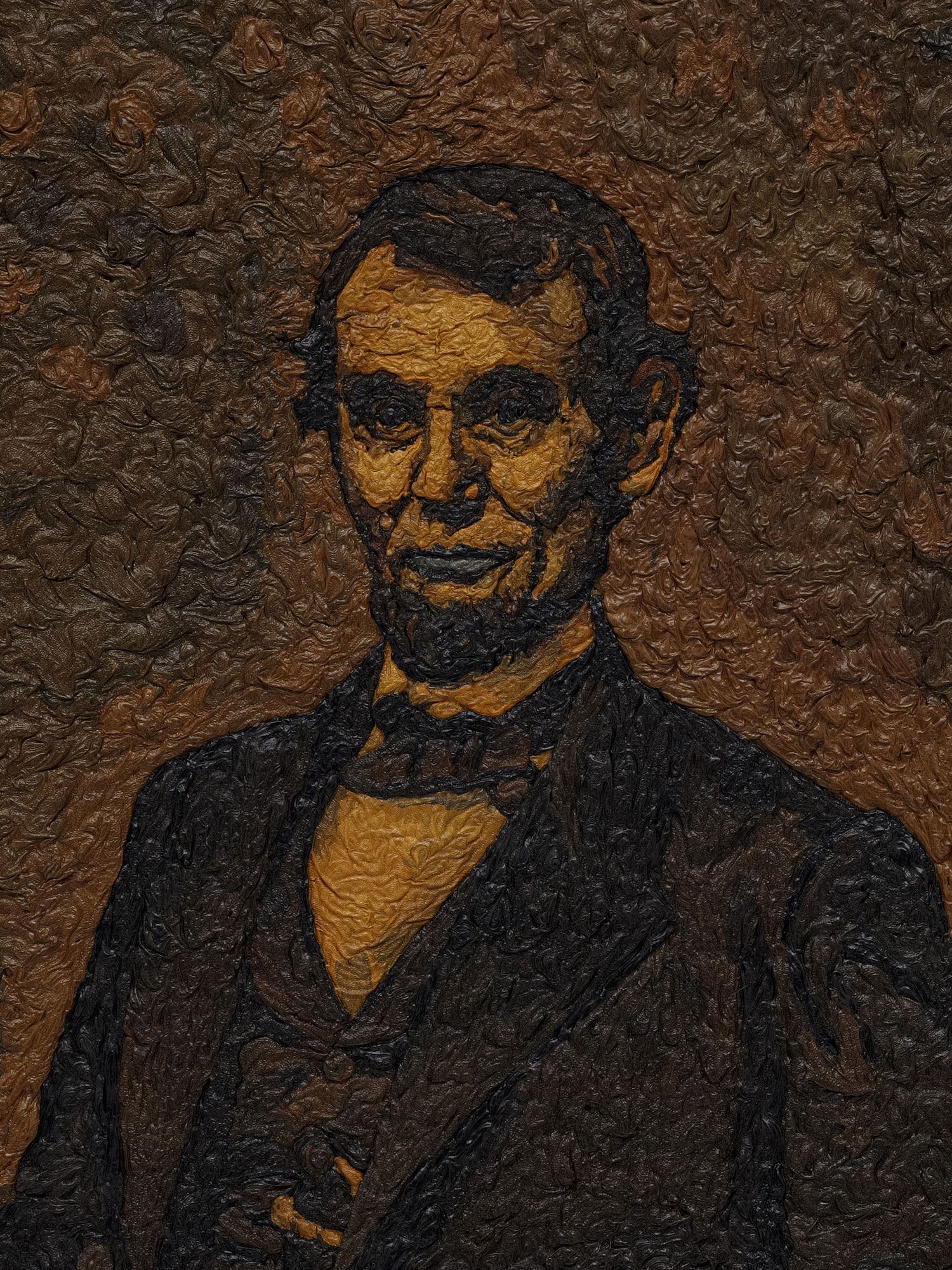

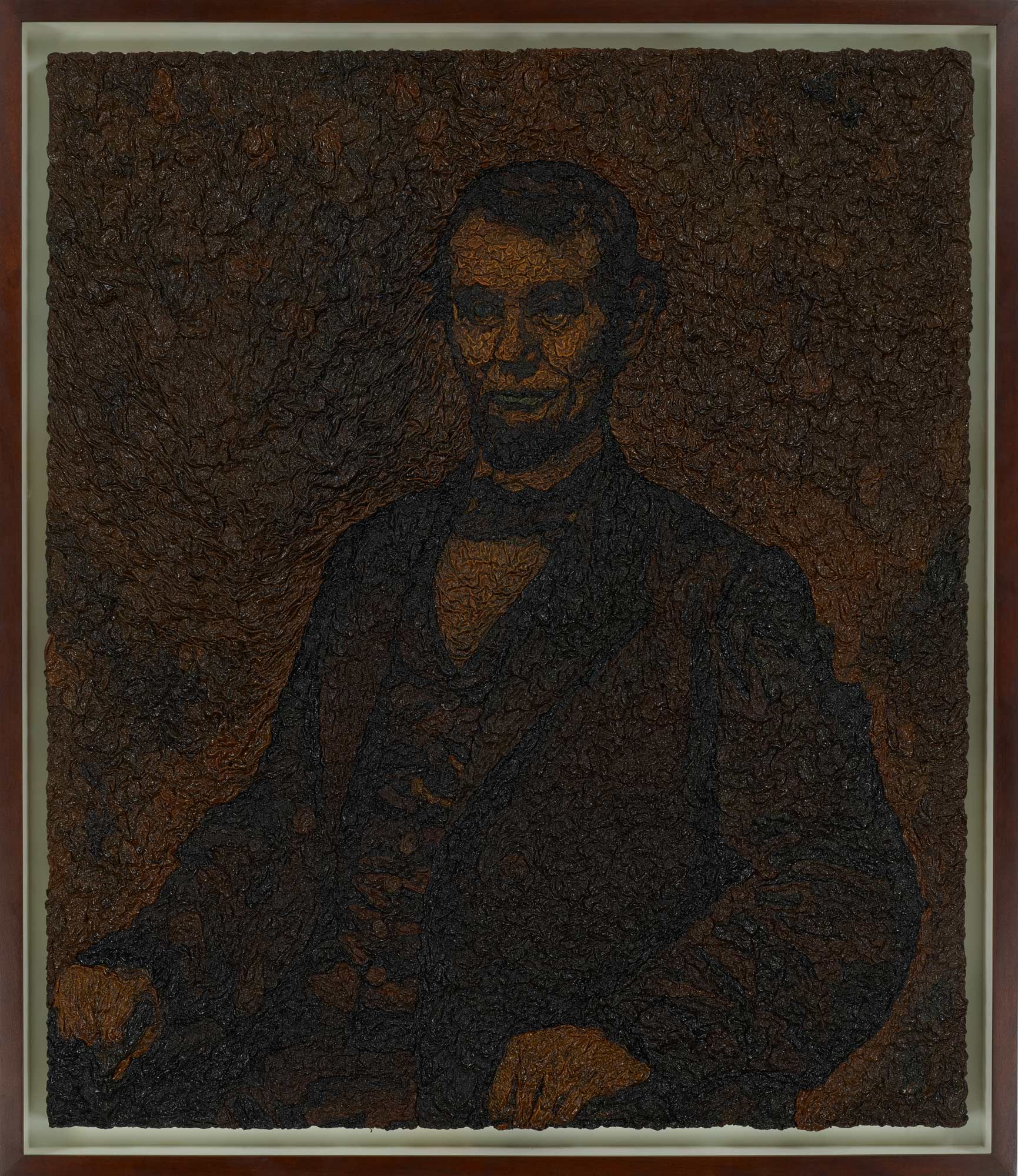

Lincoln I - Mark Alexander

Artist Mark Alexander in Conversation with Anke Kempkes

Anke Kempkes: We’ve met time and time again, en passant, in the English art world. Each time I ran into you seemed to be entirely accidental, yet we always engaged in some intense ad hoc conversation that remained memorable. Finally last year, in Fall 2012, I saw your outstanding exhibition Ground and Unground at Wilkinson Gallery in London, and I felt strongly that the time had come to take the chance and work together.

But lets start at the beginning. There are aspects of your youth and early adulthood which could be straight from an 18th century novel: a life journey that goes from growing up as a farm boy in Sussex, England, wandering a fantastical world of childhood solitude; later as a young man becoming a factory worker for aerospace manufacturing - with you passing yourself off thinly disguised as an engineer; then later passing under painful pretence as an English teacher for the Italian police… After which you travelled on swiftly failing hopes to Argentina, and got lost on the paths of unwished-for adventures. And then finally you manage the unbelievable coup of entering - without any of the required qualifications – the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford, an event which made national headlines: ‘Factory Worker goes to Oxford’…

When hearing all these stories, and more, your path reminds me of that of a cultural archetype – of the type created, for example, in Voltaire’s “Candide (ou L’Optimisme)”. As for Candide, the stories of your beginnings show an almost naïve, unspoiled, ‘ueber-imaginative’ child and young man entering a journey through adventurously changing social milieus and identities, at times being exposed to painful experiences and at others swept away like drift wood on an ocean’s current. At the same time you developed a never failing optimistic urge to improve life’s course, - and as an artist, to aspire. And like these literary characters, your story kept on fascinating people of influence and you found yourself becoming the protégé of ambitious intellectuals and philanthropic aristocrats. Again a kind of romantic 18th century form of existence…

Mark Alexander: I am an optimist by nature. If you're looking for a picaresque narrative to map my trajectory onto, you could look more to Thakeray’s Barry Lyndon or Fielding’s Tom Jones, with a little ‘Sturm und Drang’ thrown in. The narratives you refer to are largely based on an interview with the English writers Craig Raine and Adam Thirlwell.11

I grew up in Gloucestershire on a farm, and from very early on imaginings of one kind or another formed a refuge for me. Like many of my generation I was deeply influenced by a T.V. dramatization of Robinson Crusoe; it was narrated in the first person and I think this has been a huge influence on me. It has often been pointed out that I tell my story as if I’m talking about someone else; I tell it as a story. And rather than steering my life and career, it’s more as if my hand has always been open - and if a butterfly lands, I take it. I'm not sure who said it, but I remember reading: “The definition of hope is not that everything will turn out alright but that however things turn out one can make sense of them." Perhaps that was the lesson Robinson Crusoe taught me.

Looking back over my life I've been led by a curious mixture of impulse and practicalities. I've always worked to make money but perhaps a common thread is that there was something back then that made the people around me believe in me. That's the common thread in my life if I'm honest. I can't put my finger on what it was they saw in me, or perhaps I don't want to, fearing I’ll become like the millipede that wondered casually how many legs it had: ‘It took up so much of his brainpower he never moved again.’

This belief in me has given me freedom and opportunity. I did indeed move up from a silversmith apprenticeship, which was abandoned due to the silversmith becoming seriously ill after being poisoned by arsenic in the workshop. We worked with it as a cleaning agent and it has an accumulative effect, so it built up in his system over many, many years. Needless to say, I left. Then I worked in a factory, as a machine operative on a production line. I worked my way up to being a supervisor before starting and running a company that took the sharp, machined edges off components. It is a process called de-burring. My company was called "Alexander De-Burring". I had a business card made and people often thought it was my name.

I then worked for an aerospace company in Gloucestershire, operating a 3D measuring machine - it was serious stuff. There I got involved in all sorts: fighter jets, parts for space rockets… It was my job to check the first one to see if it was all set up correctly and give an 'ok' to run the batch so you had to be sure of yourself. Perhaps this is another element of my make up: certainty and conviction.

Eventually I found myself at Oxford University asking to study Fine Art. I had painted a copy of David's ‘Napoleon on Horse’. Although the faculty, then fancying itself as a progressive and conceptual department, very gently pointed out that this wasn't enough to get in at any art school, let alone Oxford. A friend told me it was the Colleges, not the faculties that hold the power at Oxford. So I went to see the head of Hertford College, a famous chaos-theory mathematician called Sir Christopher Zeeman, who interviewed me. At one point, having told him that I used mathematics at work, he pointed to a blackboard full of a seemingly complicated theory or some such. I looked and looked and could make nothing of it.

Then I noticed in the corner a little bit had been rubbed out so I jumped in and said, "I can't work this out - some of the data is missing." He looked at it and obviously thought I got to this by deduction. He walked to his telephone, phoned the faculty and announced that I was to start next week. So I was in, by luck. I got a First in the end.

AK: I believe these stories all really happened exactly the way you tell them. But do you ever feel that reality melted within the particular nature of your biographical storytelling? That these stories also became the fabric of a non-deliberate cultural strategy, in the sense that you became a ‘medium’ to social milieus and situations you met: rural class, underdogs, working class, engineering, educational systems, police, intellectual class, aristocracy, art world, - to society at large?

MA: I think if anything it's never an act of persuasion, but me being literal and light hearted. But it all happened. It's just about how I tell it. As for cultural strategies, it often depends on who’s doing the telling and how. I had one of the best poets in the English-speaking world interviewing me. Yes, I think one's story is a type of medium and, the wider the spectrum the more people can identify or attach meaning and significance. Being lucky, or seemingly so, is attractive to people and having a good story helps. You asked me if the art world is more particular… Well if the “story” of me has its own energy, you may well have to ask that question, but for me, I take my work incredibly seriously, as I have in all my jobs/incarnations. I'm a worrier, especially about the details. I think its true to say that I never set out to have a good have a good story. Indeed, when I worked in a factory I was just desperate to be supervisor. I would come in at night and keep the old machines ticking over. My shift produced more than anyone else's and the management couldn't work out why. I was so successful but it wasn't really a mystery, I just did what needed to be done and was prepared to go a bit further to do that.

AK: You started painting around 1997. After your portfolio piece for Oxford, a copy of David’s ‘Napoleon on Horse’, one of your first works was a rather mystical black and white painting inspired by the ‘genius loci’ of the Taylorian Library in Oxford where you used to study.

MA: ...Yes, that’s right, it was a tiny reading room with wall-to-wall books. I was dating a girl who was a researcher in biochemistry. We had a lot of DNA sequencing photos around our flat. The plastic Venetian blinds in the window of this reading room had little cut-outs that repeated and formed their own DNA sequence pattern and, being south facing, the sun pierced through. It was like an altarpiece to knowledge. It still exists.

AK: Then there were your early ambitious attempts to in fact paint a large-scale altarpiece - a kind of ultimate painting project. But the first work to receive prominent public recognition was your Jasmine (1997-8), a highly absorbing painting exhibited in 2002 in the cross-generations show “Painting on the Move” at the Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland. Your painting was sitting in this exhibition like an intimate monolith, showing a young woman’s face - her eyes looking devotionally upwards at a higher realm - like a Renaissance angel. A dramatic play of shadows gives a touch of contemporary orientalism and Goth, while the immediate realism of the features is rather unsettling. The famous Jasmine is a portrait of a girl-friend of the time who initiated you into the art world: “She gave me a view of the art world and what it was about – it wasn’t about copying flowers, it was about people looking for an identity, the artist and the viewers. Looking for meaning. (…) I thought you could actually give more power to something, if you painted it.”22

This work obviously meant much more than the motif it presents, it was your ‘Mona Lisa’, an allegory of initiation, a process the art audience invests much thought in and cultivates a certain voyeuristic taste for: how does an artist become an artist and at what point does it manifest?

MA: ...That's a very interesting question. I think for some artists it's about the body of work. When I had a studio at the Delfina studios in London in the late 90's, I used to argue endlessly about this with Keith Tyson and Urs Fisher. I think it was there that I first started looking for the "great work". I must have seemed very naive to them but as a painter I think you have to be realistic about where your starting-off point is. At that point I probably saw art as having a trajectory, being directional, but like the rest of the world, its now fragmented. But back then I rather arrogantly wanted to paint a picture that was clearly better than Richter. That meant looking for what I thought he had missed; emotional power. Not letting the coolness, the coldness that can dominate parts the art world, dominate me. I wanted to pick and choose but I was just starting out. I was very cheeky seeing where I could push things. But in the end that's what all of us have to do: to look for the gaps and squeeze through.

AK: Ethan Wagner once wrote that your work “stands apart” and that in front of your paintings one is alone, “and that’s just the way he wants it.”33 You used to paint very slowly, engaging with elaborate techniques and enduring processes finding the culminating point of a painting. In 2009 you engaged with an exceptional work project, which was most surprising to your audience anxiously awaiting a new rare painting output of yours. For the exhibition The Blacker Gold in Berlin you produced these giant Corten steel rings titled Shields: “Based on ancient Minoan design, conjuring connotations of jettison booster bearings, invisible escutcheons, or the great cosmic lens, these abandoned discs hunker mysteriously as Iron Age cromlechs or burial mounds.” 44

The exhibition of these mute giants confirmed in an even more dramatic physical dimension this sensation that your works repeatedly emanate, that one ‘stands alone’ confronting them. They look not unlike Richard Serra’s steel monoliths, although your pagan mythical associations with these forms remove them from the crushing wheels of the contemporary world of industry. However, looking back at your early work history as motor factory charge-hand and supervisor, quality inspector, de-burrer, finally engineer (the superb outfits you were equipped with at some point made you feel in your own words like “French nobility”55). I am reminded of Marcel Duchamp’s machine age allegories. He famously populated his work with these fantastic ‘bachelor machines’, ‘grinders’ and ‘malic molds’. Only, what Duchamp envisioned as esoteric cultural machines at the dawn of a new age, you had experienced in a direct material way in your work pre-dating your entry into the arts.

Do you think you intuitively transposed your own very real experiences from the world of engine manufacturing in an updated Duchampian way for the Shields? Another recent painting title of yours All Watched Over By Machines of Infinite Loving Grace is further suggestive of this line of thought. Or was it important for you with this project to be in touch again with the factory worlds you originally worked and lived in, with the machines and the physical impact? Or, were you rather debating your identity in the arts, the Shields ‘shielding’ you from what you had gotten into? These steel sculptures remain still today unique in your practice…

MA: The rings were a turning point for me. They were created as a formal device to separate myself from a project, which had literally obsessed me for eight years. The Shield of Achilles series also shown in that exhibition in Berlin was the final incarnation of a project to paint the “Great Work”: a golden image of myself as a defiant child, surrounded by the flames of some golden sun. The paintings materialized in the end, fantastically, but the years of attempting this standing alone, golden object, had taken its toll. In my studio I came across a long-forgotten section of the frame I had initially planned for the painting. It took me back to the days at the Aerospace plant. These giant LVA rings, Launch Vehicle Adaptors, were the rings that allowed the separation of the two parts of a rocket in space. I wanted a separation from the work so we began formalizing and simplifying my Minoan obsession. The Corten steel develops a burnt-up hue as if the rings have re-entered the atmosphere. The paintings then got made as very light, delicate, screenpaintings. There is a certain I don't know what.... I like to join in art history, jump in. I was watching the documentary "All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace", where the filmmaker Adam Curtis makes his case that computers have failed to liberate us and instead have distorted and simplified our world. His style of documentary is very invigorating. His title comes from a poem by Richard Brautigan describing a cybernetic meadow in which animals and computers were playing. It was written in the 60's I think. This title suggested in my mind Bosch's "Garden of Earthly Delights" so I had the idea of putting these two things together - a massive one-liner. I painted with as much love as I could put in. And although I wanted to break the original theme of the figures being forever young by wrinkling them, I also needed to change the title so I added the word 'infinite' as a nod to the power of computing that Brautigan couldn't have known at the time, - perhaps also to lend weight to my anxiety underlying the work.

AK: In your art school years at Oxford you had one primary goal, to paint a big altarpiece having proved to be totally contrary to the practice of the contemporary department at the Ruskin where students were primarily concerned with concept art. Since then you revisited Christian religious motifs, however at times in an obscured even mocking, or annihilating way. Was the prominent painting diptych Red Mannheim, exhibited at St Paul’s Cathedral in London in 2010 at the occasion of the anniversary of the 1940s Blitz and based on Paul Egell’s “Mannheim Altarpiece” fragment (1793-41), the fulfillment of the initial promise at the Ruskin? Can you talk a bit about this unusual project?

MA: Yes, perhaps it was. I hadn’t put the two together. I had known the remains of the “Mannheim Altarpiece” for a few years before I decided to make the works. During my years in Berlin I had become great friends with the wood-carver Bernard Lankers and he had the remains of this huge altarpiece in his studio. Namely, just the wooden back-plate which had been dismantled during the World War II. All the statues and finery had to be removed and safely stored in the Friedrichshain bunker while the back-plate languished in the basement of the Bode Museum. Unfortunately, all the works in the bunker were destroyed by fire in the hands of Russian army. All that remains is the huge phallus of a back-plate, eight meters high. In the outlines of what was once there, I found something thrilling in those absent spaces.

AK: How would you describe your involvement with Christian iconography? There have been other contemporary artists of your generation, like Kai Althoff for example, who cultivated at a certain point in their art a turn to religion. But each time that happens it seems to sit quite idiosyncratically in the contemporary art milieu…

MA: Christian iconography is in us all as artists, its hard to escape. For myself, I’m always looking to make something I can believe in. It’s true that Christian art sits idiosyncratically in the contemporary art world. I couldn't make work that was overtly religious, but if things come along like the Mannheim, in effect what's missing is the religion, - all you can see is the shadows of the bits that were once there. I mean, in the original Bosch's "Mocking Christ", Christ looks like the one doing the mocking, so I gave all the figures holes in their hands and made them all start to wrinkle.

AK: …And this was the beginning of the Bog?

MA: Interesting you ask that because there is a connection, - and yes I started then. A large number of the European bog bodies seem to have been murdered, either in a ritual or perhaps as outsiders. When I said Christian iconography is in us all as artists, I mean all artists in the West. These bodies are reminiscent of Grünewald’s crucifixions in form: the strange discoloration of their tissue and their often contorted limbs.

In the discovery of a body in this preserved state there is a sense of resurrection, these bodies are in a sense empty shadows made real, like the petrified holy limbs of Saint Teresa resting in crystal. They become relics turning man into myth. They have an after life…

AK: You have often repainted legendary masterpieces, such as Van Gogh’s “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” (1890). In your subsequent cycle of nine almost completely black paintings The Blacker Gachet (Study, and V-XIII, 2005-6) you made the original motif almost invisible, as if you wanted to draw all life out of it. When you repainted Van Gogh’s notorious sunflowers in Via Negativa V-XIII (2009) you turned their glare of color into shades of grey.

Another intervention of yours in the act of reinventing or ‘incorporating’ prominent masterpieces and icons, is the means of repetition, doubling, making twins of ever so slight variations. In your most recent show Ground and Unground you painted The Garden Boy (2012) and The Blind Garden Boy (2012). These two subtle dark variations of the motif were hanging next to each other creating an eerie presence. Executed in the dark muddy Bog painting style you established in this show, the boy looks like an otherworldly creature, like a strange animal… What function do these doublings and variations have for you?

MA: The practice first started with the ‘Dr. Gachet’ series; I painted 13 of them. I was working something through in my mind and I became fascinated by the story between the doctor and Van Gogh. The doctor, also a painter and a collector of art, seemed to have had a complicated relationship with art. It's said he often painted copies of his friend's work and signed them with their name or took their work and signed his name. Van Gogh famously initially adored Gachet but ended up hating him. At the time of painting them, I for some reason, identified with the work and, feeling so black myself, removed the color from Van Gogh's original. Feeling this would destroy the work, I was amazed to find the emotional content still there, that desperate need to feel life. After 13 paintings I stopped but, generally, if I attempt a second one, it is because I feel I’ve missed something the first time round. But it’s interesting, the original is almost always just as good and it’s just that I’ve panicked. I also painted 13 Via Negativa as a sort of homage to Van Gogh; I believe he planned to paint 13 sunflower paintings. All his large sunflower paintings were, I think, variations of the National Gallery painting, traced over or reversed. They lent themselves to the idea of multiples in my mind.

AK: Every painting or painting cycle you create seems to have an existential dimension. Your paintings appear to have an inner life of their own: be it crusty thick layers of oil paint that continue processing beyond their execution, like the Bog works; be it a densely populated canvas where the figures are highly animated as if moving in mysterious and unconventional ways - as in your adaptations of medieval motifs after Hieronymus Bosch; or be it a painting steeped deeply in an allegorical process as if its features continue to disintegrate, as in Ozymandias. How important is the material process of painting for you? Do you believe that paintings can have a (meta)physical afterlife beyond their execution?

MA: It’s very important. One’s always looking for the moment when you can feel your creation coming alive. It would be wonderful if any of them lived on in the minds of others, but the long-term afterlife of a work is ultimately dependent on its cultural leaning in the future. It's interesting what you say about the 'movement'. I was very aware that bodies that are found in Bogs are often in positions of movement or have posed themselves for death uncomfortably, so I deliberately chose images with a strong outline for death. The Reaper and The Sower from the cycle Ground and Unground almost become the antithesis of what they were in life: the Reaper harvesting death, the Sower seeding his own destruction, the sense that they are held in suspension. Actually, you've reminded me of a very strong thought I once had: I had just left Oxford when the Sensation66 show was held, and on walking out of the Royal Academy I was very excited about Damien Hirst's work. I liked how he was thinking but I thought he was missing the point. If only he could fill the frames with truly great things rather than approximating things. He takes on the Victorian model of the curiosity, but they aren't even that because you aren't curious about the subject. It would be better if he made things that can suspend your interest and ultimately these don't…If only his vitrines contained something worthwhile I thought, they would be amazing.

AK: There are moments where you formulated ideas about painting that one could almost call conceptual or post-painterly, in the sense that you want to see painting not as a purpose in itself, but to have meaning beyond its own genre limitations. You mentioned your interest in the documentary and a search for (political) content. In that sense, you are very much an artist of your generation. You often eliminated color down to black and white and grey and brown, pushing painting to an essentially material and allegorical level in an attempt to neutralize the power dynamics of time in order to resubmit or restate something. We see comparable techniques in the post-Gerhard Richter generation of painters such as Wilhelm Sasnal or Luc Tuymans. However, your work seems miles removed from their distinct agendas. How do you see yourself - as an English man – in this generational milieu of painters?

MA: Yes. Luc Tuymans, Anselm Kiefer... in my mind, they’re making cultural relics. It’s obvious that by turning an image into black and white, it almost inevitably archives it. Lending it weight. I was very interested in Anselm Kiefer at university. I see such artists as scratching, opening up, sewing up the wounds of history. Later on in Berlin, working with the curator Heiner Bastian, I got to know the work of these two artists particularly well but this approach to art is not of me. The English philosopher Malcolm Bull once wrote an essay for me. In it, he asserted that I worked away at something until all the ideas were no longer visible. I can’t say that, at the time, I felt this to be the case but I found the abstract notion rather interesting. An uncanny residue is what I would like to be left with. The bleaching of Tuymans is a formal consideration as was the earlier blurring of Richter. They were, I presume, devices to be used in order to restart or extend debates in art practice. I identify more with William Blake. Painting for me is more a song of innocence and experience than anything else. Perhaps in England, we feel more comfortable indulging our emotions than our Northern-European cousins.

AK: Apart from the Shields you hardly ever left the strict determinations of, and the dedication for, the canvas. Looking at the motifs you use which are mostly based on sources of the past, do you think painting is quintessentially a nostalgic or conservative practice? What about the nostalgia problem, being ‘dead tissue’ as Malcolm McLaren once stated? What do you think painting can still contribute to the arts today from your perspective? It is said about you that you go ‘against the current’. How important is it for you to be regarded as compatible or readable within contemporary sensibilities in art?

MA: ‘Dead tissue’. I like that. Give me some paint, I think I’d like to paint the dead tissue of our time! We don’t need to worry about nostalgia anymore. We move so fast today, it all becomes nostalgic almost immediately. Yes, I think painting is conservative - it works best when it’s just being looked at, but what it can communicate doesn’t have to be conservative.

AK: Your work often feels quite melancholic, ambiguous, even inflicted with pain, yet you describe yourself as being an optimist. Of the Ozymandias (1998-9) painting you stated: “It’s incredibly painful” and at the same time you saw it as “extremely powerful”.77 What is your idea of power in painting? Is the dark romanticism of pain related to its power? What kind of power is this? Empathy? Mortality? Or the universality of these sensations?

MA: Did I say that?! Now it’s extremely painful that I said it was extremely powerful. In Ozymandias, I wanted to produce the pain of listening to the howl of a run-over dog and capture the inner silent pain of hearing such a thing. I have to say, as a man, I fight against nihilism. Perhaps painting helps.

AK: When you started the Bog paintings, what does it mean to you?

MA: I think the Bog is now a medium through which I can search for the uncanny residue of what’s on my mind.

AK: The title of the 2012 first Bog exhibition in London was quoted after German sixteenth-century Christian mystic and theologian Jakob Böhme. Böhme introduced a cosmological system incorporating evil in its fallen state as part of a constant regeneration of the world towards a state of redeemed harmony. Your cycle of paintings included adaptations of “Adam and Eve” after Paul Egell’s “Mannheim Altarpiece” fragment (1793-41), Durer’s “Praying Hands” (circa 1508), Jean-Francois Millet’s “The Sower” (1850), Van Gogh’s “Reaper with Sickle (After Millet)” (1889) and Caravaggio’s “Narcissus” (circa 1597-99). What motivated your reception of Jakob Böhme, - again an unusual choice for a contemporary artist? And why this particular choice of motifs? The series feels a bit like a story of its own…

MA: In reality, it was only the title Ground and Unground ... The choice of images was made after working on the piece All Watched Over By Machines Of Infinite Loving Grace based on Bosch’s Garden Of Earthly Delights. I set up a little conceit that within the garden there was a Bog and in it were these works. They were all, except Narcissus and Adam and Eve, based around the notion of work: toiling the land, tending the garden. The idea is that we are our labors. This led me to conceive of American Bog. I've always been interested in where things come from; was there always something, or do things come from nothing? There's a mystical tradition of absolute nothingness, which I alluded to in the title of my sunflower paintings: Via Negativa. The Negative Way. It's allied to The Cloud of Unknowing.88 It's the Nothingness from which the Blacker Gachet stares. I remember reading about that mystic philosopher, Jakob Böhme, having a name for this Nothingness, what he called ‘Unground’. That got me thinking about grounds that aren't grounds -- grounds that change things. A peat bog is like that. So it seemed to me a good title for a project all imagining an emptiness from which things emerge.

AK: When you started thinking about your first show in New York (and for that matter in the U.S.) you moved the themes of the Bog series over to the super- or ultimate symbols of American culture and politics: Lincoln, JFK, Mickey Mouse, the American Flags. Was it again your medium-like creative thinking that made you feel these motifs strongly when imagining yourself showing in an American milieu?

MA: When I moved back from Berlin, I was given a studio by Lynn and Evelyn de Rothschild, in Berkshire. It coincided with the start of the Shields project and the end of seeking the ultimate work. I almost, overnight, turned from looking inwards to looking out. So, back in 2008, I began thinking about America as my subject. The Bog in itself was unselective; whatever or whoever fell prey. This gave me enormous freedom; there is no judgment in the selection of images outside my own aesthetic impulses.

AK: The Freakes is a less mediated motif of the American Bog series, going back to the pioneers’ history. Can you talk about this more intimate painting?

MA: Yes, this is a wonderful image. I believe they were one of the first families to settle in America. It has a ‘Madonna and Child’ feel, which I like very much. Something in it is very tender. It was, I thought, a great place to start.

AK: You painted several flags for the American Bog exhibition. Can you explain your nuancing of the motif?

MA: I’ve painted several versions of the flag from the 1777 incarnation onwards. This image, ‘bogged’, fascinates me. It’s a very organic way of painting: a lot of paint, thick with oil. There are subtle variations that occur with mood and even atmospheric conditions that affect the drying, surface, and drama. The American Bog series will have several more incarnations. I've been working on prehistoric America because I would like to do a very intimate survey of its native peoples. Right now I'm looking at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

More Articles about Mark Alexander

Reflections on the Shield of Achilles

Lincoln I Ten Years On - Mark Alexander

Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, in: Areté. The Arts Tri-Quarterly. Fiction

Poetry Reportage Reviews. Issue Seventeen, Spring – Summer 2005, p. 74-104

Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, ibid., p. 97-98

Ethan Wagner, an introduction to mark alexander, the painter, in: Mark Alexander: Alexander: The Bigger Victory, Exhibition Catalogue, Haunch of Venison, London, 2005, p. 1

Kelly Grovier, Mark Alexander, Essay, 2009, p.1-2

Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, ibid., p. 80

Sensation: Young British Artist from the Saatchie Gallery, The Royal Academy, London, 18 September – 28 December, 1997

Lives of the Artist: An Interview with Mark Alexander, ibid., p. 102

Anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century.